Forecasting Britain’s life expectancy

A baby born in 1980s Britain could expect to live into their mid-70s, placing the UK in the middle of the pack among 12 similar Western European countries. However, UK life expectancy stagnated in the 2010s, leaving the country behind its peers. In March, The Economist estimated that the combined life expectancy for boys and girls in Britain in 2022 was 81 years, only eight weeks longer than a decade ago.

If the long-term trend of improvement had persisted, The Economist noted, UK life expectancy would now be 83.2 years. While most other Western European countries also fall short of this mark due to the Covid pandemic, the UK lags behind. The report estimated that even after adjusting for the general European slowdown and factoring in Covid-related deaths, there remain 250,000 deaths specific to Britain.

They acknowledged caveats in their analysis, such as the reliance on population projections that had not yet incorporated changes from the latest census. Yet such caveats cannot obscure the fact,” found the report, “that something has gone badly wrong in the past decade, and that large numbers of Britons have lived shorter lives as a result”.

The Economist proposed various factors that UK policymakers should consider, but we wanted to get an idea of which ones mattered most. Our group of forecasters — which includes Jared Leibowich, winner of The Economist's World Ahead 2022 forecasting challenge — proposed and evaluated potential solutions for the UK's lagging life expectancy.

First, we established a baseline by asking our forecasters to predict UK life expectancy in 2030. The average prediction was 82.6 years, an increase of 19 months from today's life expectancy. They anticipated a bounceback from the pandemic-induced dip, but believed it would still be held back by the NHS' challenges, which were too deeply-rooted to be resolved within seven years. They also considered the possibility of dramatic changes that could significantly alter their estimates, such as medical breakthroughs or large-scale catastrophic events.

We then asked forecasters to give their estimates under different conditions, to see if there were any factors they thought were critical.

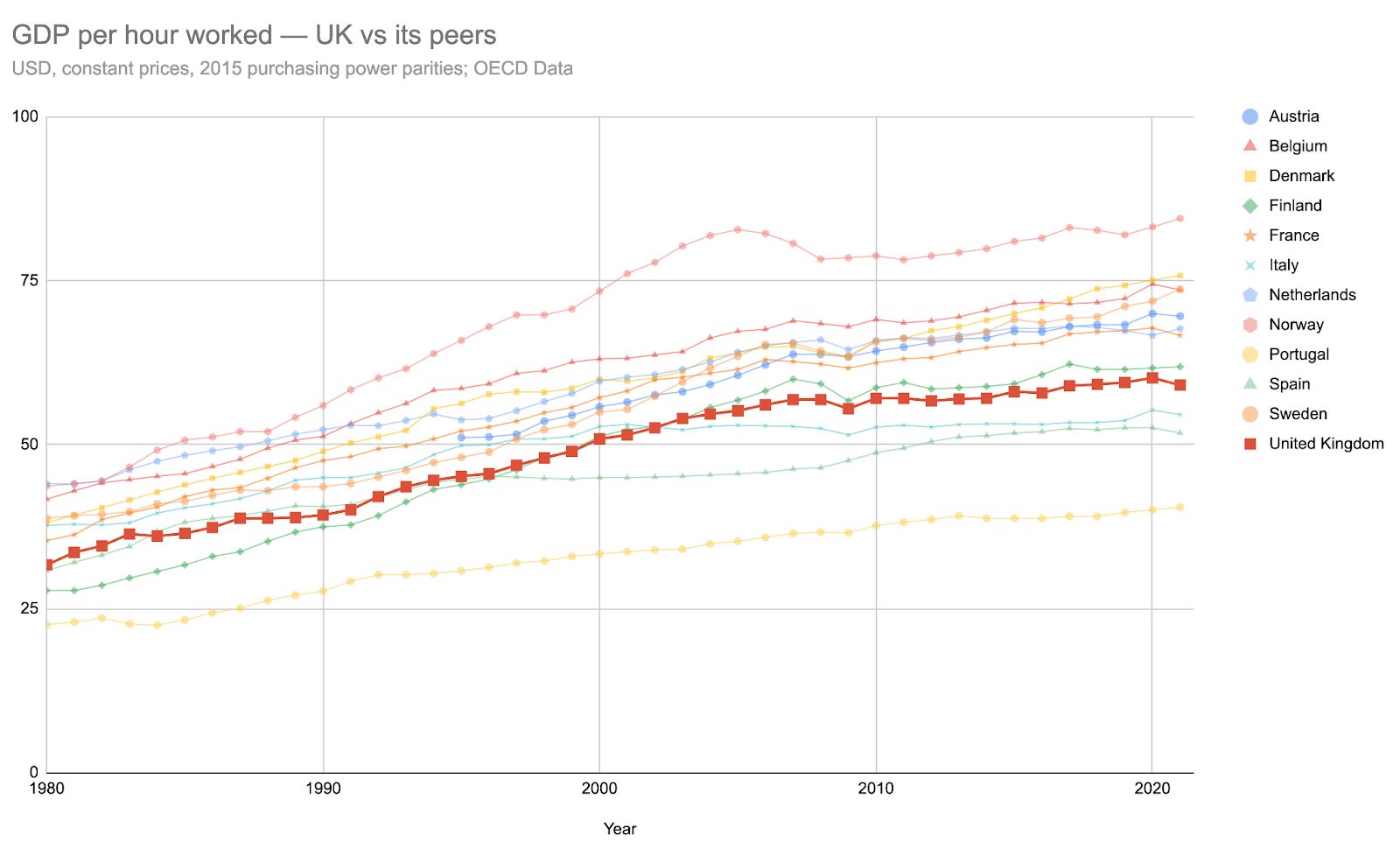

Improved economic productivity: +1.8 years, but unlikely

UK productivity has been a long-standing issue, ranking 10th out of 13 Western European countries in 2021, generating $59.1 of GDP per hour worked, according to OECD data (which indexes on 2015 US dollars and adjusts for purchasing power). Portugal, for context, was bottom, by some distance, at $40.5; Norway, at $84.5, was top. How do forecasters’ outlooks change if British productivity reached more than $65 of GDP per hour worked?

Our forecasters considered whether the UK productivity was likely to average that over 2025–2030, but they were generally pessimistic. For context, Norway and Sweden needed just 3 years for their productivity figures to increase from $59/h to $65/h, while the Netherlands needed 6 years, Denmark 7 years, and France 13 years (due to the 2007–8 financial crisis hindering growth).

An analysis into UK productivity warrants a separate report (and we accept commissions for those interested in funding such work), but our forecasters’ initial thinking puts less than 25% chance on this rate of productivity growth, mostly due to obstacles such as high housing and energy costs.

However, if the UK's average productivity were to reach this level between 2025 and 2030, forecasters expected this “would translate into both improved lifestyles, better public services, and improved healthcare” and would correlate with an additional 1.8 years of life expectancy.

If such improvements took place, our forecasters thought this would push British life expectancy to little more than a year behind the average of its 12 peers. (In 2021, Britain was 1.65 years behind those peers.)

This suggests that forecasters don’t expect gains to be particularly specific to the UK. Some forecasters suggested that the likeliest cause of fast-rising productivity was transformative AI, which, like other technologies, would be a tide that lifted all public services, including healthcare, across Europe. However, forecasters expected Britain may outperform its peers this decade as a result of healthy growth in its pharmaceutical and biotech sectors.

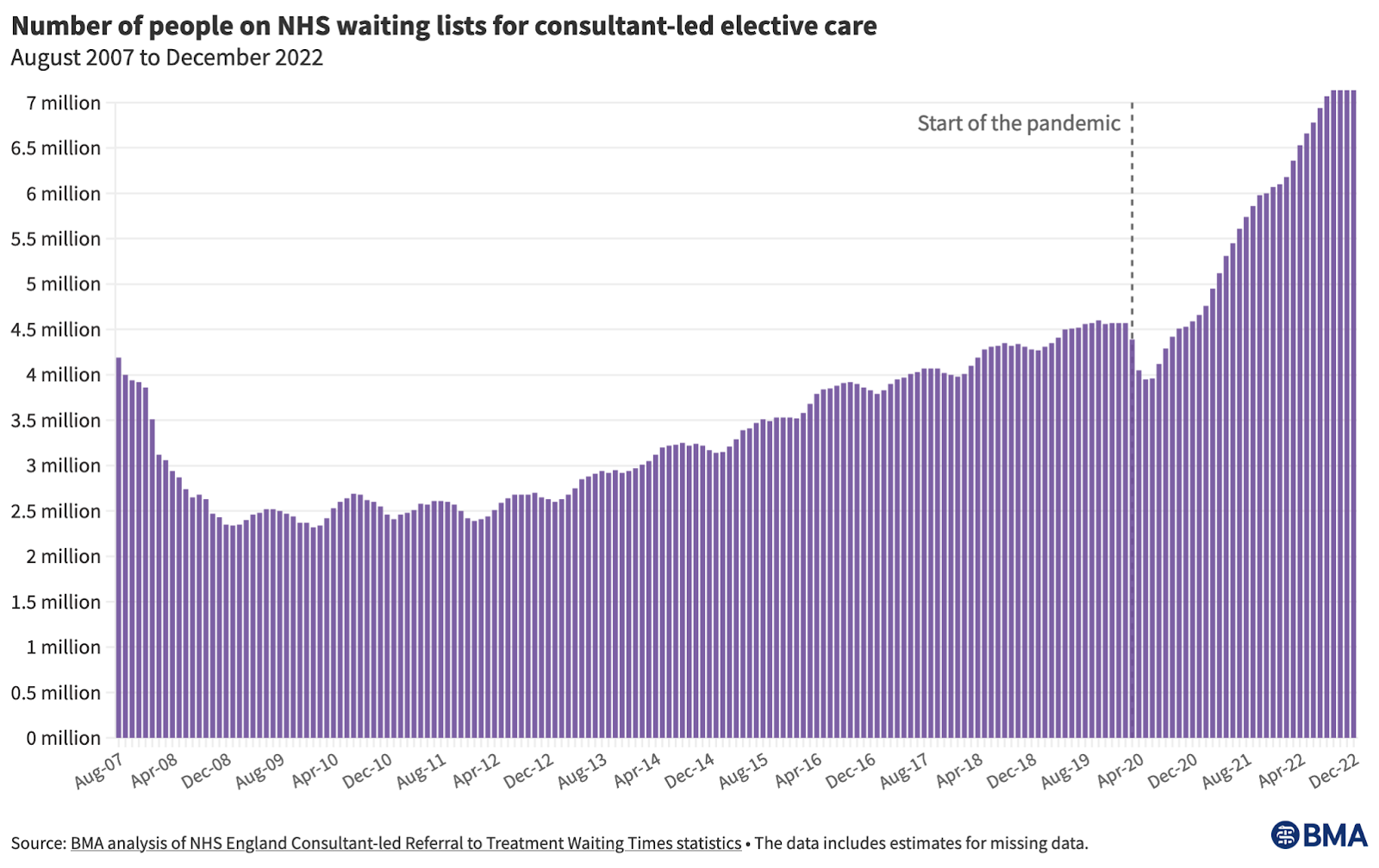

Big reduction of the NHS waiting list: +1 year, but very unlikely

Source: BMA

Currently, 7.2 million Britons are on the NHS's elective care waiting list. Could the average backlog be cut down between 2025 and 2030 to less than 3 million? As seen in the figure above, there were consistently fewer than 3 million people on the waiting list from 2008 to 2013, but then substantially more from the mid-2010s onwards (especially after the pandemic).

Our forecasters thought it was highly unlikely the UK would return to 2010 levels soon, with none of them rating it above a 10% likelihood for 2025–2030.

If this reduction were achieved, it would be, as one forecaster put it, “a staggering achievement” that would signal “a massive increase in efficiency at all levels”. Forecasters reckoned it would add an additional year to the UK’s life expectancy, as “it would likely signal that there has been a massive increase in efficiency at all levels and that the problems of healthcare access and staff shortages, amongst other problems, have been solved”. Another was more reserved, saying that this “would show an increase in care or a shift to online/telemedicine” and that “the impact would be beneficial but not massive”.

The most likely scenario is that the UK does not meet that waiting list figure, with life expectancy figures 1.3 years shorter than its peers’. “The delays will cause many premature deaths,” wrote one forecaster, “especially through delayed cancer diagnosis”.

Semaglutide uptake: +1.2 years, and a comparatively easy intervention

A new class of weight-loss drug has received plenty of coverage since being approved for NHS use in March. These drugs are GLP-1 agonists, and the best-known is semaglutide, often sold as an injectable drug under the name Wegovy. It inhibits appetite and slows digestion, leading to significant weight loss. Given that 25.9% of Britons are classed as obese, the widespread adoption of GLP-1 agonists – e.g. by 20% or more of the country’s adult population – might be a key condition for improving the UK population’s longevity.

This scenario was rated as having a 38% likelihood, as it would reduce the number of cardiovascular events bringing about people's early deaths, and would overall reduce the burden on the NHS and the taxpayer by a significant margin. As such, they estimate it would increase British life expectancy by 1.2 years (when compared to the scenario in which fewer than 20% of Britons have taken GLP-1 agonists).

In order to intuit whether such high uptake was likely, forecasters looked to other prescription rates. A 20% uptake would imply roughly 11 million adults receiving a prescription, and one forecaster points out that this isn’t entirely unprecedented: “the most widely prescribed drug in the UK is Omeprazole, a drug used to treat heartburn amongst other things — about 13–14m people have a prescription every year”.

Forecasters explained why this uptake scenario would affect their estimates. One said that they were “forecasting around an extra 7/10ths of a year of life expectancy gains ... where the drugs are in widespread common usage and we're able to make serious dents amongst overweight people dying in their 50s/60s of heart attacks and strokes”. Another explained:

The short-term impacts on life expectancy would probably only be very marginal and affect the most seriously obese, but with 7 years until the question resolves that is a fair amount of time for the reduced impacts of obesity to have a positive effect. I think there would be a measurable impact, as years without living with higher blood pressure, increased risk of heart disease etc is clearly good for people, and it would be targeting some of the least healthy people in society.

But short-sighted government parsimony might inhibit the rollout, they warned:

A very quick calculation [...] the cost would be over £9bn a year just to treat 20% of the population. The NHS says obesity costs the organization £6.1bn a year, but £27bn to wider society. Political silliness about paying a single or small number of drug companies such a large amount of money might also cause hesitancy.

Another, who thinks such a large uptake is unlikely (at 10%) estimates that “less than 8% of UK adults will even meet the NICE criteria in 2030”. Others agreed that the main barrier would be NICE changing the eligibility requirements. One forecaster points out that “the UK has no real culture of widespread off-label use and individual payments for drugs outside of the NHS prescribing framework” but says they “don't really have too many serious doubts about the popularity of semaglutide, conditional on it actually being widely pushed”.

Labour coming to power: +0.3 years, and it seems likely

Did forecasters think the political party in power would make a difference? Our forecasters had 85% confidence in a Labour prime minister taking office after the next general election, and they also expected that a Labour prime minister would improve life expectancy, if only to a small extent. “I expect a Labour government would fund the NHS more than the Conservatives would,” said one forecaster. Labour government’s policies, another forecaster added, are more likely to lower the rate of “deaths of despair” (i.e. those from drugs, suicides, accidents and alcohol).

Of the overall impact of a Labour government, though, the same forecaster said: “I think the effect has to be pretty slight,” noting that improving life expectancy specifically is unlikely to be a political priority for them, let alone something they’ll pursue effectively.

More preventative public health funding

Preventative health interventions are widely thought of as being better-value than waiting for problems to develop, and is highlighted as an area for improvement in The Economist’s analysis. For the last decade, funding for public health has come from the Department for Health and Social Care and is given to local authorities via annual grants. The local authorities then use it for preventative services, such as those to do with smoking, drugs, alcohol and sexual health, alongside other functions, such as children’s services (e.g. supporting children in care).

But the grant has been shrinking. On a real-terms per person basis, it has been cut by 24% since 2015/16. It was £3.3bn in 2020-21, and £3.5bn in 2021-22.

What if it went up? Increasing the public health grant from its 2021-22 value of £3.5bn to £5bn didn’t perceptibly change forecasters’ outlooks for life expectancy (when measured in 2030). A few expected it would correlate with small increases (of around 0.2 years) but the grant itself, a forecaster pointed out, is strongly weighted towards children’s services, which have a less direct effect on life expectancy than the services relating to obesity and smoking:

The amounts spent on anti-smoking and anti-obesity campaigns are negligible amounts (less than 10% of the total Public Health Grant) and it's not clear to me that increasing the amount spent on this would do anything measurable to life expectancy.

Conclusions

In 2021, the UK was 1.65 years behind the average life expectancy of its peers, and none of our forecasters expected that this gap would be closed by 2030. They think the discrepancy is likely to shrink, since the UK’s divergence from its peers was temporarily exacerbated by the pandemic. However, the most optimistic forecaster — who believed that the difference was likely to shrink to under 1 year — cited the ongoing health impact of Covid-19 as a reason why it would stay wider than the 0.83-year discrepancy witnessed in 2019.

Economic conditions were considered critical for many forecasters. Explaining their pessimistic outlook, they pointed to specific economic circumstances of Britain’s recent history (being hit particularly hard by the financial crisis; Brexit; years of low productivity) and medium-term future (“Britain has the most advanced decarbonization policies and most offshore wind capacity, but… no ability to build new nuclear, exploit new fossil fuel finds, or even build out its electricity grid to cope with rising electricity demand due to the shift to electric vehicles”).

Are there grounds for optimism? Squint and you might see it. “I expect general economic stagnation and relative decline to continue for another decade before an eventual policy reversal,” concluded one forecaster.

“The peer countries will probably carry on getting richer and living longer,” said another. “It seems very unlikely that the UK will be above average, but — with huge healthcare reform — they might return to being just-below-average (like in the Blair years)”.

Based on these conditional forecasts, the most effective way to increase life expectancy would be to improve the state of the UK’s economy. However, the easiest and most feasible method would be the wide distribution of GLP-1 agonists, such as semaglutide.